I haven’t been feeling very inspired this year. Most of the things I write are meant to inspire in some way or at least point towards where hope might be discovered. Last week I wrote an annual report for work and was aware that part of the purpose of that was to express gratitude for work done by great people in the last year and it was also about capturing a positive vision of the year to come that people might get behind. It was relatively easy to make that hopeful, but I am finding that kind of positivity more challenging when it comes to writing this blog and Sunday sermons in particular.

Round 2 of President Trump, which began in January, had me addicted to news feeds for a while. “Drill, baby drill,” he said on day 1, confirming his lack of regard for the sustainability of our planet. It wasn’t as memorable as his claim that the concept of global warming was invented by the Chinese to undermine US markets, or his quip about rising sea levels creating more ocean front properties, but it was just as depressing.

In the weeks that followed I found myself scrolling through news feeds and getting more and more alarmed. J.D. Vance visited Europe and was spectacularly offensive and angry, revealing a mindset that seemed to see the 1930s not so much as a warning from history but a manual for success. President Zelenskyy, whose country was invaded by Russia, visited the White House and was bullied by Trump and Vance in a scene that was less reminiscent of The West Wing than Goodfellas. It seemed like the gangsters were in charge.

Meanwhile not so far behind the scenes, Elon Musk and Trump collaborated to remove voices of dissent from positions of influence, and continued to work towards the monopolisation of information channels so that disinformation could become more the norm. They tried to label this free speech when it is anything but. Indeed, in my day job I often teach critical thinking classes, and it really does feel like there are a lot of people not only in the United States but around the world who desperately need to develop their fact-checking skills. As that great President of another era, Abraham Lincoln, once said, “The problem with quotes on the internet is it’s hard to verify their veracity.”

In those early weeks I watched the news and followed social media feeds too much. I would look at my phone and immediately feel angry at what was going on but I was always desperate to find out more. After a while, though, I realised that this was not doing me any good and decided to withdraw from news and social media not completely but enough to connect to wider realities and ways of seeing the world. I had a stack of books that I had been given for Christmas. Perhaps these would help.

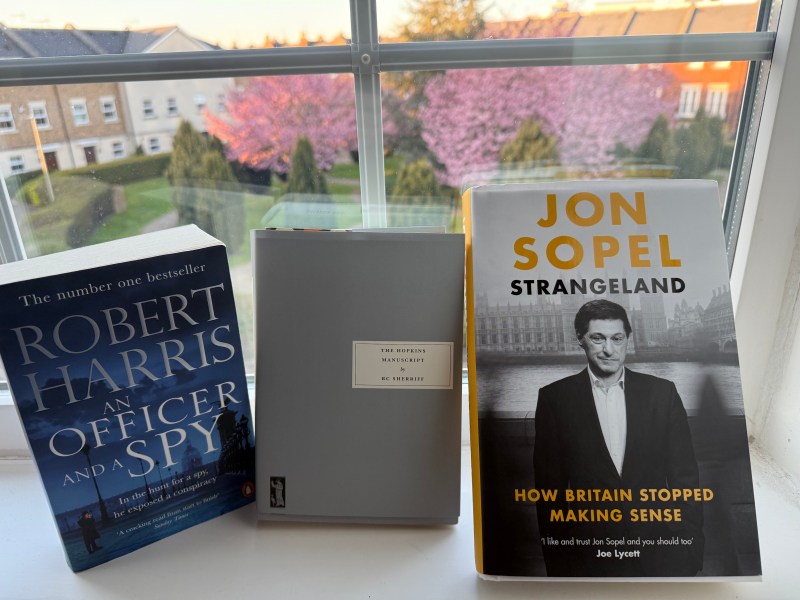

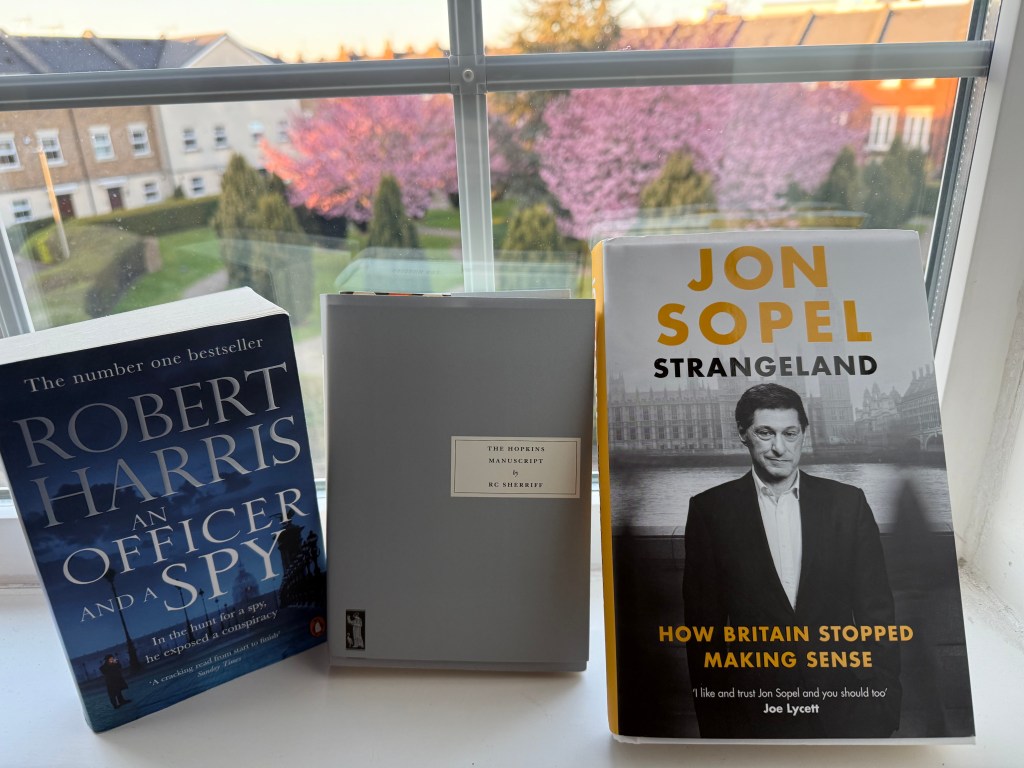

The first book I read was Robert Harris’ compelling novel An Officer and a Spy, which is about the Alfred Dreyfus scandal that rocked France at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. It’s a riveting book but at its heart it is a warning about what can happen when people prioritise their allegiance to particular individuals or personalities over systems of law and justice. It made me think of the current situation and was thus not escapism.

I read Jon Sopel’s excellent book Strangeland, which to be fair didn’t even promise to be escapism because it is his thoughts on returning to the UK after living in the US for several years and finding that he didn’t recognise the place anymore. At first I found the style of the book a little annoying, as Sopel writes in speech rather than prose, meaning his punctuation is all over the place. However, I effectively received a telling off from Stephen King on this when I read his book On Writing, in which he argues that punctuation should not always be made to dress up in formal attire; sometimes we should allow it a day in leisure-wear or even a full on pyjama day in which semi-colons are locked in a literary chest of drawers and capital letters are not made to get up off the couch because sometimes the effort is too much.

To return to Strangeland, however, Sopel shows how intertwined the stories of Britain and the United States are and at the book’s heart is incredulity about how an event as clearly undemocratic and hate-fuelled as the January 6th riots on the Capitol building could now be so easily brushed under the carpet of history. My thought by the end was ‘You ain’t seen nothing yet.”

Another book I read for escapism is The Hopkins’ Manuscript, which is a terrific science fiction novel first published in 1939. The world is about to suffer a terrible catastrophe as the moon is on a collision course for Earth and the end of everything is predicted. In the event quite a lot of people survive the catastrophe but (spoiler alert) then different countries go to war over the mineral rights and real estate value of the moon. Responding to human suffering by going after mineral rights and real estate. Who would do such a thing?

And that’s the trouble isn’t it? We cannot escape from the world as it is no matter how much we try and nor should we be able to, for in troubled times there are people who need our support, issues to campaign on and needs to be met, but we do need to look after ourselves so perhaps a step away from the news scroll is no bad thing.

As I write this it’s a beautiful spring day in Cheltenham, X is long since deleted from my phone and today I have had good conversations with nice people. It’s not all bad news out there and if I can’t always be persuasively hopeful, I can at least point towards those who can. Kate Rusby has recorded a new song with Barnsley youth choir – you may find it more inspirational than this blog.